I hope you like strong cheese. This sweet-looking little guy had to move into the isolation ward at my house when it threatened to stink up everything in sight. I enjoy that decaying-mushroom smell at dinner time, but not when I open the fridge to hunt for breakfast. My husband couldn’t take it, either, so he put the cheese, still in its cardboard box, inside another lidded container and banished it to the outdoor fridge.

A couple of days later, I retrieved it, brought it to room temperature, and cut out a wedge. Oh, man. As the young people say, this cheese rocks. Graindorge’s Camembert au Calvados looks like a conventional Camembert, but your nose tells you something else is up. Under the robust porcini aroma is a fruity smell, a hint of fermenting apples or cider. At first the scent seemed peculiar—not a typical cheese fragrance—but it grew on me. The creamery has added Calvados to the cheese curds, and that appley scent persists as the cheese matures.

Graindorge, a century-old enterprise in the Normandy region, is the sole producer of this cheese, although others make Calvados-flavored Camembert by different methods. The family-owned company boasts online of being passed de père en fils (from father to son) since 1910, but that claim needs an update as the 28-year-old Mathilde is about to take the reins from her father.

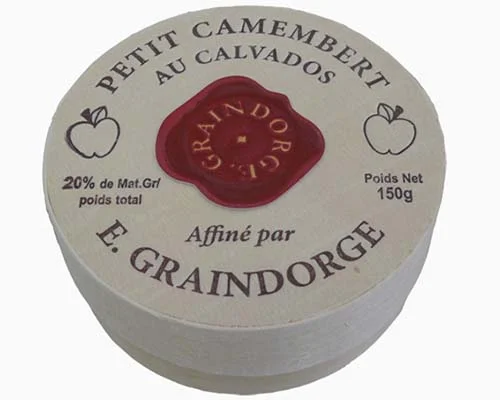

To the eye, Camembert au Calvados looks straightforward, with the classic size and shape (8.8 oz/250 g) of Normandy’s most famous cow’s milk cheese. It nestles in its own round lidded box, which preserves humidity and keeps the bloomy rind from drying out. The ivory paste is supple and buttery, with pinhead-size openings. You can see in the photograph that the rind is lightly dappled with tan markings, as if the Penicillium candidum on the rind is dying back a bit. That’s a sign of maturity—some might say over maturity, but I tend to like this style of cheese when it gets surface dappling. If you had probed the cheese, you would have felt a lot of give, another indication of ripeness.

Note also that the rind is evenly thin and that the paste, or interior, is not pulling away from it. I’m happy to see that. Judging by what I see from newbie cheesemakers, these two features are not easy to achieve. I also think Graindorge has done an admirable job of getting compelling aroma and reliable maturation into a soft-ripened cheese made with pasteurized milk. So often the soft-ripened cheeses from France taste dead on arrival; they have zero scent and never seem to ripen. Camembert au Calvados smells beefy and garlicky, just on the right side of rot, and the texture is voluptuous.

Some stores are selling a smaller-format (5.3 oz/150 g) Camembert au Calvados, but if you have a choice, choose the larger cheese. It has a more pleasing proportion of rind to interior. A glass of dry French cider would be the obvious beverage choice, but a saison makes a nice match, too. Belgium’s Saison Dupont, with its pear-cider aroma, was delicious with it.

Look for Camembert au Calvados at Bay Cities Italian Deli (Santa Monica); Berkeley Bowl West; Dean & DeLuca (St. Helena); Diablo Foods (Lafayette); La Fromagerie (S.F.), Gourmet Cellar (Livingston, MT); Milk Pail Market (Mountain View); Monsieur Marcel (L.A.); Oliver’s Markets (Santa Rosa and Cotati); Pacific Market (Sebastopol); Pasta Shop (Oakland); Surfas (Orange County); Vintage Grocers (Malibu); and Woodlands Market (Kentfield).

The Eighty Percent

As California’s drought persists, we can expect to see higher cheese prices. Without rain, there is no grass. Without grass, there is no hay. Without their own hay, livestock owners have to buy more feed. And that means higher milk prices.

I asked a prominent cheesemaker what percentage milk represented in her cost of production. Eighty percent, she told me. Eighty percent! I had no idea. Her creamery makes goat cheese, and she pays more than $4 a gallon for the milk—almost four times the price of cow’s milk. The whole planet is experiencing a goat’s milk shortage, she said. Even so, she can’t charge four times the price of cow cheese for her goat cheese—or even twice as much. Who would buy?

Paying eighty percent of your production costs for one ingredient doesn’t leave much for staff, equipment, insurance, rent. This particular cheesemaker has other income streams, but many goat dairies and goat cheese producers are struggling, she told me, and some won’t survive.