The ruffles are eye-catching but you don’t need a special scraper to appreciate Tête de Moine. It’s a delightful cheese even when not curled into frilly rosettes. That said, I’m going to treat myself to a girolle—the shaving device—one of these days because, well, what a conversation stopper. The girolle’s Swiss inventor died four years ago, at 91, aware that his clever tool had sent sales of Tête de Moine soaring. Annual production is now 150 times what it was when his girolle debuted in 1982. I just listened to an old interview with the inventor and was charmed to hear about his lightbulb moment and be reminded of how good this cheese is.

Nicolas Crevoisier grew up in a small village on the Swiss side of the Jura mountains. Tête de Moine was the local cheese, with roots that purportedly go back 800 years, to the Abbey of Bellelay. When Crevoisier was young, the cheese was so expensive it was practically sacred and locals reserved it for celebrations. Tradition called for the man of the house to serve it, painstakingly shaving it into paper thin rosettes with a knife. Crevoisier remembers his father being expert at it, but such know-how was vanishing with the oldtimers.

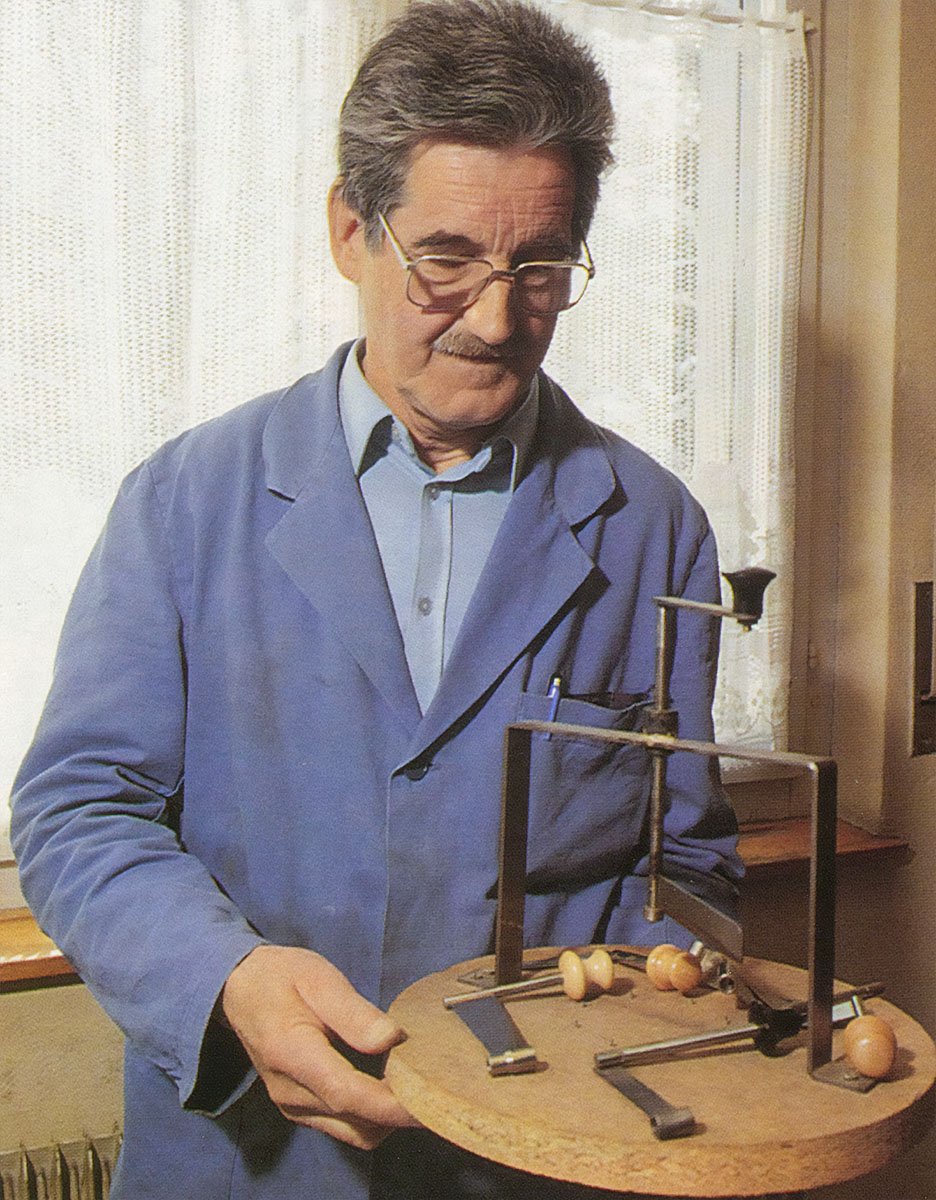

Nicolas Crevoisier with original girolle

The young cheese lover became a mechanical engineer whose company made (and still does) precision tools for watchmakers and others. In the mid 1970s, he attended a local reception for some Canadians, and it took so long for the hosts to shave enough Tête de Moine for the group that he begin noodling the idea of a tool that would do the job faster.

Crevoisier spent three years on the prototype, after landing on the blasphemous tactic of anchoring the wheel with a dowel. By 1982, he had a commercial product. He christened it girolle, another name for the chanterelle mushroom, which the cheese shavings resembled. Not convinced it would find an audience, he ordered only 300 boxes. He sold 15,000 girolles the first year. The business has since sold three million.

Crevoisier patented his device but spent the next two decades suing copycats. The patent expired in 2002 and now other companies, such as Boska, manufacture similar tools.

Ruffled or not, Tête de Moine is an enticing cheese, made with raw milk, matured at least 75 days, and washed repeatedly with a brine containing Brevibacterium linens. These “good” bacteria give the rind a salmon hue and the interior a robust aroma of peanut butter, fried shallots and roast beef. The girolle, with its rotating blade, releases maximum aroma and makes sheets so thin and silky that they melt on your tongue. A sharp cheese plane won’t make ruffles, but it’s a fine alternative.

The foil-wrapped Tête de Moine cylinders we get in the U.S. weigh about 2 pounds but you only need a half-wheel for your girolle. A friend tells me she successfully substitutes the sheep’s milk P’tit Basque when she can’t find Tête de Moine. I’ve recently seen pre-shaved rosettes of Tête de Moine in plastic clamshells at Whole Foods; I’m not sure that’s the best way to experience this cheese but it will certainly dress up your cheese board.

A dry Alsatian Pinot Gris or a malty brown ale would be a nice match for Tête de Moine. It’s an excellent melter so save any scraps for grilled cheese or fondue.